-

- Wallabag.it! - Save to Instapaper - Save to Pocket -

The evolutionary mysteries of a rare parasitic plant

New study maps the strange genomes of Asia-Pacific Balanophora species, giving new insights into the evolution of parasitic plants and an unconventional role of plastids.in OIST Japan on 2025-12-10 12:00:00 UTC.

-

- Wallabag.it! - Save to Instapaper - Save to Pocket -

Cancer loses its sense of time to avoid stress responses

New insights into mitotic stopwatch show how cancer escapes cell death and cell division arrest.in OIST Japan on 2025-12-10 12:00:00 UTC.

-

- Wallabag.it! - Save to Instapaper - Save to Pocket -

What is the future of organoid and assembloid regulation?

Four experts weigh in on how to establish ethical guardrails for research on the 3D neuron clusters as these models become ever more complex.in The Transmitter on 2025-12-10 05:00:38 UTC.

-

- Wallabag.it! - Save to Instapaper - Save to Pocket -

Earthquake Science and Fiction Collide in Tilt

On our Best Fiction of 2025 list, Emma Pattee imagines Portland’s worst Earthquake in her debut novel Tilt

in Scientific American on 2025-12-09 21:15:00 UTC.

-

- Wallabag.it! - Save to Instapaper - Save to Pocket -

RFK, Jr., Questions Safety of Approved RSV Shots for Babies

FDA officials are newly scrutinizing several approved therapies to treat RSV in babies despite the fact that these shots were shown to be safe in clinical trials

in Scientific American on 2025-12-09 20:15:00 UTC.

-

- Wallabag.it! - Save to Instapaper - Save to Pocket -

Human Missions to Mars Must Search for Alien Life, New Report Finds

A major new study lays out plans for crewed missions to Mars, with the search for extraterrestrial life being a top priority

in Scientific American on 2025-12-09 20:00:00 UTC.

-

- Wallabag.it! - Save to Instapaper - Save to Pocket -

NASA’s JWST Spots Most Ancient Supernova Ever Observed

Astronomers have sighted the oldest known stellar explosion, dating back to when the universe was less than a billion years old

in Scientific American on 2025-12-09 18:00:00 UTC.

-

- Wallabag.it! - Save to Instapaper - Save to Pocket -

Pompeii House Frozen Mid-Renovation Reveals Secrets of Roman Cement

Lime granules trapped in ancient walls show Romans relied on a reactive hot-mix method to making concrete that could now inspire modern engineers

in Scientific American on 2025-12-09 17:17:00 UTC.

-

- Wallabag.it! - Save to Instapaper - Save to Pocket -

One of Kazakhstan’s top nuclear physicists also leads his nation in retractions

Maxim Zdorovets

SourceThe head of a nuclear physics institute in Kazakhstan now has 21 retractions to his name — most of them logged in the past year — following dozens of his papers being flagged on PubPeer for data reuse and images showing suspiciously similar patterns of background noise, suggesting manipulation.

Maxim Zdorovets, director of the Institute of Nuclear Physics in Astana, has written or coauthored 480 papers indexed on Scopus, and one analysis puts him as the third most cited researcher in Kazakhstan. His prolific publication record has been linked to Russian paper mills, though those claims are unverified. Zdorovets has defended his work in a series of online posts, arguing the imaging similarities come from technical issues and that his own analyses prove image manipulation did not occur. He did not respond to Retraction Watch’s request for comment.

The latest retraction for Zdorovets came last month when Crystallography Reports retracted a study containing electron microscope images “highly similar” to those published a year earlier in a now-retracted paper in the Russian Journal of Electrochemistry by a similar group of authors. Both papers also included images that closely resemble ones Zdorovets and his colleagues presented at a nanomaterials conference in Ukraine in 2017. In each instance, the images were meant to be showing different materials.

According to many of the retraction notices, Zdorovets’ papers have noise in the data that appears unusually similar across several figures. In 2023, a PubPeer commenter who pointed out suspicious patterns in a 2017 Materials Research Express paper triggered a lengthy exchange with IOP Publishing, the journal’s publisher, which conducted three separate investigations into the paper. Initially, IOP said their subject-matter expert consultant found no sign of “intentional alteration,” and the company decided to take no action.

Commenters pushed back, and in June 2024, the publisher sought opinions from three more experts, one whom they described as an “absolute expert in this area.” The experts concluded the raw data submitted by the authors showed “distinct backgrounds.” The publisher again decided not to act.

In September 2024, Maarten Van Kampen, a data sleuth in the Netherlands, weighed in on the PubPeer thread, agreeing that the background noise looked identical and also pointing out similarities between data in the 2017 paper and another since-retracted paper by a similar group of authors, including Zdorovets, in 2018.

Finally, this June, IOP Publishing acknowledged that their experts had “failed to compare the raw data provided by the authors with the published data,” despite earlier claims to the contrary. The journal retracted the article for containing identical background noise in the X-ray diffractions, which they said “can be indicative of image manipulation.” They also noted the raw data the authors provided didn’t match the paper’s data, meaning they could find “no evidence of the experiments being undertaken.”

Asked about the investigations, Kim Eggleton, IOP Publishing’s head of peer review and research integrity, said the first set of experts had been given raw data in a different file format than the later group of experts. The newer group also included a specialist in X-ray diffraction and two of the PubPeer commenters who first raised concerns. They had requested the specific format “so they could assess the concerns in greater depth,” she said.

In August this year, the paper’s second author, Marat Kaikanov, posted in the PubPeer thread that he hoped his colleagues responsible for the X-ray measurements would “be able to confirm the accuracy” of the results. Kaikanov told us he couldn’t evaluate the flagged data firsthand because those experiments were outside his area of responsibility, but said his own contribution “was completed diligently and in full.”

While he didn’t weigh in on that PubPeer exchange, Zdorovets has engaged with some other criticisms on the platform, where 85 papers he coauthored are flagged. In one detailed response, he dismissed an allegation the background noise in X-ray diffraction images were duplicated.

“We were puzzled by such an unexpected question,” he wrote, “since there is no and cannot be any reasonable sense to somehow artificially change the background on the spectra mentioned in the question.” In his comments on PubPeer, he says he analyzed both spectra and “can firmly say that they are not duplicated in any part,” though he acknowledged a “high degree of similarity” in the backgrounds. His explanation is that the samples were so thin that the instrument recorded signals from the table beneath them, resulting in the resemblances — a claim which Van Kampen, the Dutch data sleuth, calls “unhinged.”

“As sleuths we get gray hair from these arguments,” Van Kampen told Retraction Watch, adding that persistent denial helps delay or even prevent retractions. He referred to a COSIG guide that states, “No matter what, no two XRD patterns will feature the same noise pattern, even if they are collected from the same sample on the same instrument with the same settings.”

The 2018 paper, published in Journal of Nanoparticle Research, was retracted in December 2024 because of seemingly identical background noise in two figures. When the journal asked the authors for the original data, they found what was provided “differs substantially” from what had been published, according to the notice.

In PubPeer comments made after the retraction, Zdorovets expressed frustration over a lack of “scientifically-grounded counter arguments” and called the accusations “unfounded.” He said he had provided the original data to the journal and said there was “no conflict” between the submitted files and the figures in the article. “We strongly disagree with the decision to retract,” he wrote.

Zdorovets has defended his work in reports he posted on his personal ResearchGate, including what he says is a mathematical analysis of the data in three retracted papers showing no duplications. His coauthors have argued that similarities come from reduced image quality and say critics misunderstood how X-ray diffraction data were processed, claiming similarities arose from how the figures were viewed or plotted.

In a statement to Retraction Watch, a researcher who has collaborated with Zdorovets and wished to remain anonymous said ”neither I nor the authors of these papers, including Prof. Zdorovets, performed XRD measurements personally,” and that the measurements came from a specialist at the institute whose data they had no reason to doubt. They suggested post-processing procedures such as smoothing, background correction and normalization might explain the observations. They said all the X-ray diffraction data now undergo internal verification.

The collaborator said the group felt “deliberately targeted” on PubPeer since “so-called ‘reviewers’ on PubPeer presuppose our guilt in advance.”

The research group remains open to constructive dialogue, the collaborator wrote, and maintains the observed problems are ones of method, not falsification, problems which “could and should have been resolved through correction rather than full retraction.”

While background noise duplication is the most frequent issue raised around Zdorovets’ work, seven of the retraction notices also refer to data being reused across several papers that allegedly report on different materials and experiments. One 2018 paper, published in Ceramics International, is a complete duplication of another paper published in Materials Research Express a few months earlier by a similar group of authors. The editor called the duplication a “misuse of the scientific publishing system.” A 2019 paper in Journal of Alloys and Compounds, duplicates data and tables published two months earlier in Nanomaterials. That earlier paper, now also retracted, used images published another month earlier in Vacuum.

In 2023, Zdorovets won a Scopus prize supported by Elsevier and the government of Kazakhstan to recognize leading Kazakh researchers. He was also recently elected to the National Academy of Sciences of Kazakhstan.

Retraction Watch Sleuth in Residence David Robert Grimes contributed analysis to this article.

Like Retraction Watch? You can make a tax-deductible contribution to support our work, follow us on X or Bluesky, like us on Facebook, follow us on LinkedIn, add us to your RSS reader, or subscribe to our daily digest. If you find a retraction that’s not in our database, you can let us know here. For comments or feedback, email us at team@retractionwatch.com.

Processing…Success! You're on the list.Whoops! There was an error and we couldn't process your subscription. Please reload the page and try again.in Retraction watch on 2025-12-09 16:15:00 UTC.

-

- Wallabag.it! - Save to Instapaper - Save to Pocket -

A look under the hood of DeepSeek’s AI models doesn’t provide all the answers

A peer-reviewed paper about Chinese startup DeepSeek's models explains their training approach but not how they work through intermediate steps.in Science News: AI on 2025-12-09 16:00:00 UTC.

-

- Wallabag.it! - Save to Instapaper - Save to Pocket -

OpenAI’s Secrets are Revealed in Empire of AI

On our 2025 Best Nonfiction of the Year list, Karen Hao’s investigation of artificial intelligence reveals how the AI future is still in our hands

in Scientific American on 2025-12-09 15:00:00 UTC.

-

- Wallabag.it! - Save to Instapaper - Save to Pocket -

Black Hole Caught Blasting Matter into Space at 130 Million MPH

X-ray space telescopes caught a supermassive blackhole flinging matter into space at a fifth of the speed of light

in Scientific American on 2025-12-09 14:45:00 UTC.

-

- Wallabag.it! - Save to Instapaper - Save to Pocket -

Some irritability is normal. Here’s when it’s not

Irritability is a normal response to frustrations, but it can sometimes signal an underlying mental health disorder, like depression or anxiety.in Science News: Psychology on 2025-12-09 14:00:00 UTC.

-

- Wallabag.it! - Save to Instapaper - Save to Pocket -

This Weekend’s Geminids Meteor Shower Should Be Spectacular

As far as annual meteor showers are concerned, 2025 has saved the best for last. This year’s Geminids are not to be missed

in Scientific American on 2025-12-09 13:00:00 UTC.

-

- Wallabag.it! - Save to Instapaper - Save to Pocket -

Space-Based Data Centers Could Power AI with Solar Energy—at a Cost

Space-based computing offers easy access to solar power, but presents its own environmental challenges

in Scientific American on 2025-12-09 12:30:00 UTC.

-

- Wallabag.it! - Save to Instapaper - Save to Pocket -

OIST Hosts Second International Administration Forum, Welcoming 33 Participants From 18 Universities and CAO

How can Japanese universities strengthen their global engagement? At OIST’s 2nd International Graduate School Administration Forum, 33 participants from across Japan gathered at OIST to explore practical strategies for the future of internationalization, examine shared challenges, and experience OIST’s unique model for international graduate education, firsthand.in OIST Japan on 2025-12-09 12:00:00 UTC.

-

- Wallabag.it! - Save to Instapaper - Save to Pocket -

Mathematicians Crack a Fractal Conjecture on Chaos

A type of chaos found in everything from prime numbers to turbulence can unify a pair of unrelated ideas, revealing a mysterious, deep connection that disappears without randomness

in Scientific American on 2025-12-09 12:00:00 UTC.

-

- Wallabag.it! - Save to Instapaper - Save to Pocket -

Breakthrough in Digital Screens Takes Color Resolution to Incredibly Small Scale

These miniature displays can be the size of your pupil, with as many pixels as you have photoreceptors—opening the way to improved virtual reality

in Scientific American on 2025-12-09 11:45:00 UTC.

-

- Wallabag.it! - Save to Instapaper - Save to Pocket -

The philosophical misconception behind the LLM cult (or why LLMs will always bullshit)

There is this idea that if a large language model (LLM) is trained on a large corpus of text, then it knows whatever knowledge is in that corpus. Improving the performance is then essentially a matter of scaling: as you expand the database, you expand knowledge, assuming the statistical model is fine enough (aka many parameters). You can then ask questions and the LLM will answer according to the knowledge in the corpus.

This might sound like a reasonable view, but it is based on a misconception about the nature of knowledge. Indeed, an implicit assumption is that the corpus is logically consistent. But what if it contains a proposition as well as its contradiction, for example the Earth is round and the Earth is flat? In that case, the trained LLM cannot produce consistent answers; it will answer differently, depending on how it is cued – an annoying experience that many users are familiar with.

The natural answer would be to build a high-quality corpus, e.g. by selecting academic textbooks, rather than conspiracy theories. Unfortunately, this is a naïve view of scientific knowledge, one that has been thoroughly debunked by over a century of philosophy of science. It is the view that science is a linear accumulative process: you add observations, and you add deductions, and if you check those assertions, then you get a consistent, certified, corpus of knowledge. Knowledge, then, is constituted of propositions that derive directly from observations, plus what you can logically deduce from those (this is essentially logical positivism). It follows that, if you add a book to a corpus of books, you necessarily increase knowledge, by exactly one book (assuming there is no redundancy).

As intuitive as it might sound, this view is utterly false. It has been shattered on historical grounds by Thomas Kuhn (see also Hasok Chang for more recent work), and on philosophical grounds by various philosophers, such as Lakatos, Quine and others. In science, theories get superseded by other theories that contradict them. At any given time, there are always different theories that coexist, and diverging interpretations of facts. Science is a debate. Human knowledge is contradictory, and science is about trying to resolve those contradictions, not accumulating true propositions. Any working scientist knows that any field is full of paradoxes, internal contradictions and diverging views. It follows that no scientific corpus is internally consistent.

If you build a statistical model of an inconsistent corpus, you do not resolve those contradictions. Instead, what happens is that, depending on context (the prompt), the model will predict one thing or its contrary, possibly within the same session, with apparent confidence – indeed, if you merge two confident propositions, you get a confident contradiction, not doubt. An LLM will always bullshit. Scaling alone (whether of the corpus or of the model) cannot solve this problem.

in Romain Brette on 2025-12-09 08:30:56 UTC.

-

- Wallabag.it! - Save to Instapaper - Save to Pocket -

Professor Grune’s diet of dodgy blots

As German TV asks Tilman Grune what he will eat in the future, I have other questions for him.in For Better Science on 2025-12-09 06:00:00 UTC.

-

- Wallabag.it! - Save to Instapaper - Save to Pocket -

Insights on suicidality and autism; and more

Here is a roundup of autism-related news and research spotted around the web for the week of 8 December.in The Transmitter on 2025-12-09 05:00:44 UTC.

-

- Wallabag.it! - Save to Instapaper - Save to Pocket -

2025 Likely to Tie for Second-Hottest Year on Record

Europe’s climate agency said 2025 is likely to be the second or third hottest on record

in Scientific American on 2025-12-09 03:00:00 UTC.

-

- Wallabag.it! - Save to Instapaper - Save to Pocket -

How to juice your Google Scholar h-index, preprint by preprint

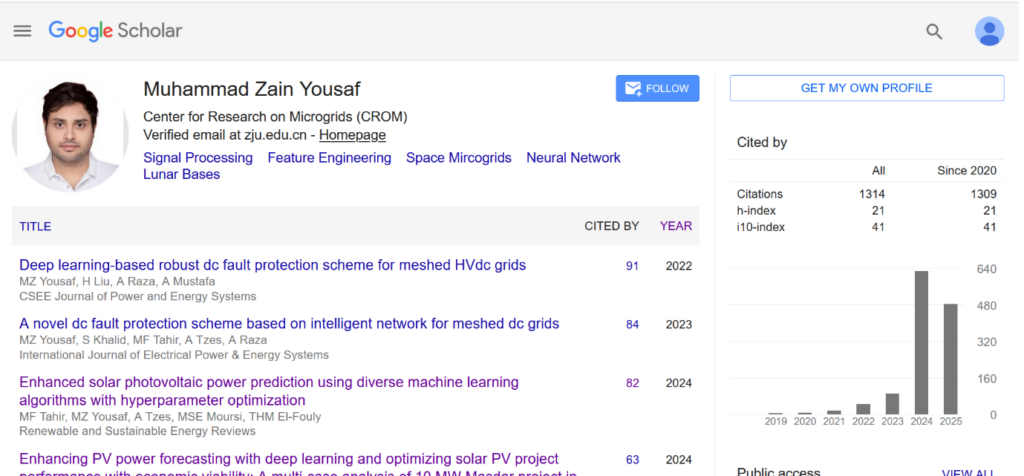

A screenshot of Yousaf’s Google Scholar profile before it was removed. Muhammad Zain Yousaf, a postdoc at Zhejiang University in Hangzhou, China, became a scholar of note overnight. Or so it would seem, based on his now-defunct Google Scholar profile: From a modest 47 in 2022 and around 100 in 2023, Yousaf’s citations jumped to 629 in 2024. His h-index, a measure combining publication and citation numbers, took off accordingly, reaching levels typical of a senior academic.

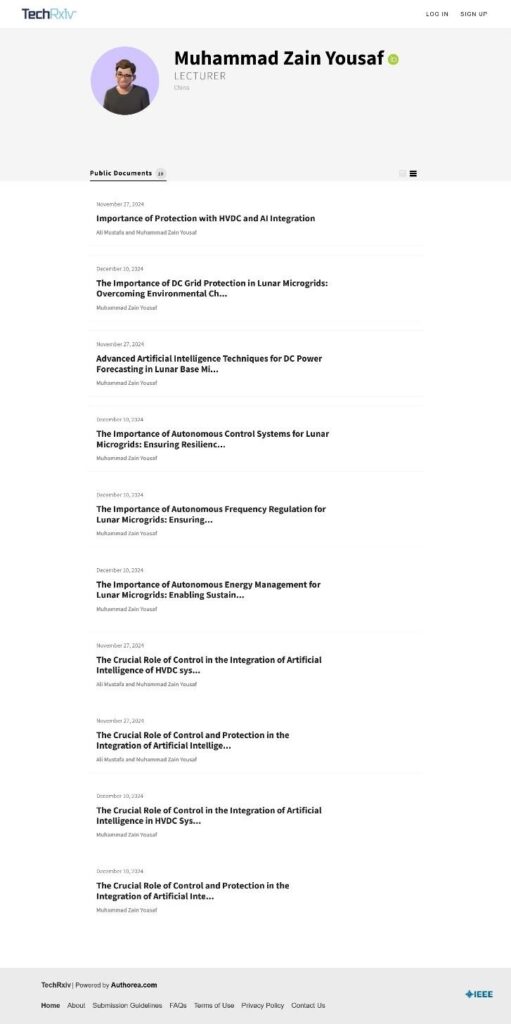

But another researcher smelled a rat and took a closer look at Yousaf’s publications. In just two days, Yousaf had uploaded 10 short documents to TechRxiv, a preprint server hosted by the U.S.-based Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineers, or IEEE. Each of the documents was chock-full of self-citations. In five cases, Yousaf was an author on all 37 papers in the reference list; the rest of the time, his publications made up nearly two-thirds of the reference list.

”Many of these documents appear to be low quality, as evidenced by their lack of coherence and technical quality,” the concerned researcher, who asked to remain anonymous, said of the preprints in an email to TechRxiv last December.

The researcher added that Yousaf’s actions were ”a clear attempt to manipulate citation metrics on external platforms such as Google Scholar” and ”undermine the credibility of TechRxiv as a platform for genuine academic contributions.”

One year later all of the documents remain on IEEE’s server. “IEEE is aware of the concerns regarding these papers and is investigating,” Francine Tardo, corporate spokesperson for the organization, told us.

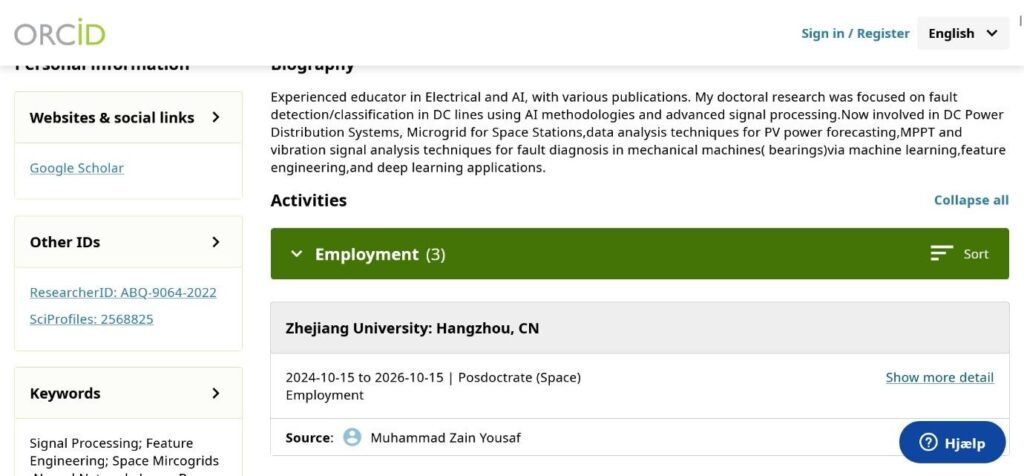

Yousaf’s profile on TechRxiv still lists 10 documents uploaded within days of each other in 2024. (Click to enlarge) Yousaf, an electrical engineer, did not acknowledge our emails laying out the allegations against him and asking for an interview. But on the day we first contacted him, the researcher’s Google Scholar page, which listed his h-index as 21, was taken down; his name on TechRxiv was shortened to “Yousaf” and delinked from his ORCID profile; and the ORCID entry describing his current position at Zhejiang University – “Posdoctrate (Space)” (sic) – disappeared. Several more entries were removed later. A recent paper lists Yousaf’s affiliations as the School of Aeronautics and Astronautics at Zhejiang University and the Center for Research on Microgrids (CROM) at Huanjiang Laboratory in Zhuji.

Google Scholar has become the go-to source of publication metrics for academics evaluating new job applicants, even at renowned universities in the United States and England. But the tool is exceedingly easy to game for those looking for a shortcut to impressive numbers – the service will index even non-existent papers cited in preprints – as researchers have shown again and again (and again and again and again). We wrote about a high-profile computer scientist in Spain, Juan Manuel Corchado, who had done just that in 2022.

To get a better sense of how this tactic inflated the researcher’s h-index, David Robert Grimes, one of Retraction Watch’s Sleuths in Residence, scraped data from Google Scholar on September 10, when Yousaf’s h-index was 19. Excluding self-citations slashed the index to 13, and removing sources with no or minimal peer review, such as preprints and conference proceedings, brought it down to 12. When Grimes excluded both self-citation and sources without peer review, Yousaf’s h-index dropped to 9, a reduction of more than 50 percent. (Yousaf’s h-index according to Scopus, the Elsevier citation database, is 14, up from 13 in November.)

The position at Zhejiang University shown in this screenshot of Yousaf’s ORCID profile has since been deleted. “This is far from the first time somebody has used non-peer-reviewed archives to manipulate Google Scholar,” said Reese Richardson of Northwestern University, who studies scientific fraud. “Google Scholar has made it very clear they don’t intend to fix this. They have known about this for 10 years.”

Google did not respond to requests for comment.

Yasir Zaki, a computer scientist at New York University Abu Dhabi in the United Arab Emirates, recently published a study describing different ways Google Scholar metrics can be manipulated. Yousaf’s case, Zaki said, is “in line with what we have seen in the past.”

”Many of our suspicious authors were uploading documents to either ResearchGate or Authorea,” Zaki told us. “On a related note, arXiv has banned computer-science review papers that have not been published for the exact same reason, because some authors are using this as a way to inflate their citations.”

Zaki said he and his colleagues built a tool using data from OpenAlex to visualize collaboration patterns for specific researchers. The tool shows Yousaf had nearly 130 unique coauthors with whom he collaborated only once, and that in 2025, Yousaf had as many as 120 new unique coauthors – both abnormally high numbers, according to Zaki.

Graham Kendall, a computer scientist and deputy vice chancellor at Mila University in Malaysia who writes frequently about publications ethics, also noted a steep rise in citations in 2025 on Yousaf’s Scopus profile. Such an increase raises “a red flag,” Kendall told us.

In Richardson’s view, metrics gaming “is going to happen so long as there’s a pressure for citations. The question is, who is going to willingly participate in it? So TechRxiv has decided that they’re going to, Google Scholar has decided that they’re going to.”

Like Retraction Watch? You can make a tax-deductible contribution to support our work, follow us on X or Bluesky, like us on Facebook, follow us on LinkedIn, add us to your RSS reader, or subscribe to our daily digest. If you find a retraction that’s not in our database, you can let us know here. For comments or feedback, email us at team@retractionwatch.com.

Processing…Success! You're on the list.Whoops! There was an error and we couldn't process your subscription. Please reload the page and try again.in Retraction watch on 2025-12-08 20:07:44 UTC.

-

- Wallabag.it! - Save to Instapaper - Save to Pocket -

AI Slop Is Spurring Record Requests for Imaginary Journals

The International Committee of the Red Cross warned that artificial intelligence models are making up research papers, journals and archives

in Scientific American on 2025-12-08 18:00:00 UTC.

-

- Wallabag.it! - Save to Instapaper - Save to Pocket -

Exclusive: Springer Nature retracts, removes nearly 40 publications that trained neural networks on ‘bonkers’ dataset

The dataset contains images of children’s faces downloaded from websites about autism, which sparked concerns at Springer Nature about consent and reliability.in The Transmitter on 2025-12-08 17:00:14 UTC.

-

- Wallabag.it! - Save to Instapaper - Save to Pocket -

Chernobyl’s Shield Guarding Radioactive “Elephant’s Foot” Has Been Damaged for Months

The site of the world’s worst nuclear disaster remains damaged, but so far, radiation levels outside the plant have not increased, according to officials

in Scientific American on 2025-12-08 16:47:00 UTC.

-

- Wallabag.it! - Save to Instapaper - Save to Pocket -

Watch Lava From Hawaii’s Kilauea Volcano Obliterate a Webcam

Hawaii’s Kilauea, one of Earth’s most active volcanoes, sent lava fountains spewing into the air, obliterating a U.S. Geological Survey camera

in Scientific American on 2025-12-08 16:25:00 UTC.

-

- Wallabag.it! - Save to Instapaper - Save to Pocket -

Tsunami Warnings Issued in Japan after Magnitude 7.6 Earthquake

Japanese officials said to expect a tsunami of up to 3 meters in some areas after a magnitude 7.6 earthquake struck off the east coast of Japan

in Scientific American on 2025-12-08 16:20:00 UTC.

-

- Wallabag.it! - Save to Instapaper - Save to Pocket -

Vitamin K Shot Given at Birth Prevents Lethal Brain Bleeds, but More Parents Are Opting Out

Vitamin K injections have prevented deadly brain bleeds in infants for more than 60 years. New research shows refusal rates have recently jumped nearly 80 percent

in Scientific American on 2025-12-08 16:00:00 UTC.

-

- Wallabag.it! - Save to Instapaper - Save to Pocket -

Rewire Your Career: Emily Cook

Meet Emily Cook, Founder of FOUND, whose journey from finance to neuroscience-informed coaching reveals how brain science transforms performance and why recovery and inclusion are key to sustaining it.in Women in Neuroscience UK on 2025-12-08 15:00:26 UTC.

-

- Wallabag.it! - Save to Instapaper - Save to Pocket -

GLP-1 drugs failed to slow Alzheimer’s in two big clinical trials

Tantalizing results from small trials and anecdotes raised hopes that drugs like Ozempic could help. Despite setbacks, researchers aren’t giving up yet.in Science News: Health & Medicine on 2025-12-08 13:30:00 UTC.

-

- Wallabag.it! - Save to Instapaper - Save to Pocket -

Infrasound Tech Silences Wildfires before They Spread

A new sound-based system could squelch small fires before they grow into home-destroying blazes

in Scientific American on 2025-12-08 11:45:00 UTC.

-

- Wallabag.it! - Save to Instapaper - Save to Pocket -

Vaccine Controversies and Measles Outbreaks, Space Pollution, Puppy Power

Vaccine controversies, space pollution, and puppy power.

in Scientific American on 2025-12-08 11:00:00 UTC.

-

- Wallabag.it! - Save to Instapaper - Save to Pocket -

Seeing the world as animals do: How to leverage generative AI for ecological neuroscience

Generative artificial intelligence will offer a new way to see, simulate and hypothesize about how animals experience their worlds. In doing so, it could help bridge the long-standing gap between neural function and behavior.in The Transmitter on 2025-12-08 05:00:35 UTC.

-

- Wallabag.it! - Save to Instapaper - Save to Pocket -

Death by Fermented Food

Some fermenting foods can carry the risk of a bacterium that produces an extremely strong toxin called bongkrekic acid

in Scientific American on 2025-12-07 08:00:00 UTC.

-

- Wallabag.it! - Save to Instapaper - Save to Pocket -

Why Are ADHD Rates On the Rise?

More than 1 in 10 children in the U.S. have ADHD, fueling debate over the condition and how to treat it

in Scientific American on 2025-12-06 13:00:00 UTC.

-

- Wallabag.it! - Save to Instapaper - Save to Pocket -

Free radicals caught in the act with slow spectroscopy

New experimental setup detects the faint signals of electrons, shedding new light on the physics of photodegradation and other long-term photoemission processes.in OIST Japan on 2025-12-06 12:00:00 UTC.

-

- Wallabag.it! - Save to Instapaper - Save to Pocket -

How Close Are Today’s AI Models to AGI—And to Self-Improving into Superintelligence?

Today’s leading AI models can already write and refine their own software. The question is whether that self-improvement can ever snowball into true superintelligence

in Scientific American on 2025-12-06 12:00:00 UTC.

-

- Wallabag.it! - Save to Instapaper - Save to Pocket -

Weekend reads: ‘The fall of a prolific science journal’; Clinical trials by ‘super-retractors’; ‘How to Study Things That May Not Exist’

Giving Tuesday was this week, and, like many organizations, we asked for your support. The work we do is funded in part by your donations. If you value our work in rooting out scientific fraud and misconduct, exposing serial offenders, spotlighting how to fix broken systems — and bringing you this newsletter — please consider showing your support with a tax-deductible donation.

The week at Retraction Watch featured:

- Iraqi journal suspected of coercion, two others dropped from major citation databases

- Authors retract Nature paper projecting high costs of climate change

- The case of the fake references in an ethics journal

- Number of ‘unsafe’ publications by psychologist Hans Eysenck could be ‘high and far reaching‘

- Glyphosate safety article retracted eight years after Monsanto ghostwriting revealed in court

- Nature paper retracted after one investigation finds data errors, another finds no misconduct

Did you know that Retraction Watch and the Retraction Watch Database are projects of The Center of Scientific Integrity? Others include the Medical Evidence Project, the Hijacked Journal Checker, and the Sleuths in Residence Program. Help support this work.

Here’s what was happening elsewhere (some of these items may be paywalled, metered access, or require free registration to read):

- “The fall of a prolific science journal exposes the billion-dollar profits of scientific publishing.”

- “A small number of influential authors … account for a significant proportion of retracted clinical trials,” researchers find.

- “The Problem of Wrongly Identified and Nonverifiable Nucleotide Sequences and Cell Lines in Research Papers,” and why they’re “canaries in a coal mine.”

- Professor “cleared of data fabrication allegations after investigation.” A link to our coverage of the “statistically improbable data” tied to the researcher.

- “New NIH Policies Make It Easier to End Grants, Ignore Peer Review.”

- “Holding science to account: A qualitative study of practices and challenges of watchdog science journalism,” coauthored by our Ivan Oransky.

- Can X discourse be used to predict which papers will be retracted? Researchers investigate.

- “Reviewers are better equipped to detect fraud than editors,” researchers say in response to study of coordinated fraud. See our earlier coverage.

- “Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence – and that affects what scientific journals choose to publish.”

- “There is a danger in not being critical about the efforts that go under sleuthing,” psychologist Ioana Alina Cristea says. “The boundaries of what they are doing are very porous.”

- “Riding the Autism Bicycle to Retraction Town.”

- “Court sets aside” university researcher’s “plagiarism case against colleague.”

- An advent calendar by Anna Abalkina, the creator of our Hijacked Journal Checker, that gives you a chance to spot issues in academic publishing.

- “Disquiet over ‘PhDs by publication’ diminishes doctorate’s prestige.”

- MDPI makes three “stealth corrections” of the peer review record after professor flags the papers as “being affected by a review mill.”

- “Gender disparities in publishing: how networks, occupational self-efficacy and the university shape the gender publication gap among professors in Germany.”

- The Royal Society journal Philosophical Transactions uses cover art that is AI generated, says researcher.

- “Diabetes ‘Trade Journals’: A Rather Heterogeneous Affair.”

- “AI use widespread in research offices, global survey finds.”

- “Elsevier shutdown looms Down Under as open access talks collapse.”

- “The CNRS is breaking free from the Web of Science.”

- UK funding body “opens up grant proposal data to explore using AI to smooth peer review.”

- “The U.S. Is Funding Fewer Grants in Every Area of Science and Medicine.”

- Researchers propose the “BEYOND Guidelines for Preventing and Addressing Research Misconduct.”

- “Publish or perish: making sense of India’s research fraud epidemic.”

- “Research Integrity in an Era of AI and Massive Amounts of Data“: Authors expand on previous papers “and offer more details on solutions.”

- How the authors of recent World Health Organization guidelines on infertility treatment used the Retraction Watch Database to check for potentially falsified data.

- “Low success rate in early career grants” in Australia “deeply disappointing.”

- “Universities told they must lead fight against scientific ‘paper mills’” in Poland.

- Chinese ministry “kicks off a campaign to crack down on misconduct in academic papers.”

- “WHO said what? Non-robust standards in citing WHO and EPA drinking water guidelines.”

- “How I contributed to rejecting one of my favorite papers of all time.”

Like Retraction Watch? You can make a tax-deductible contribution to support our work, follow us on X or Bluesky, like us on Facebook, follow us on LinkedIn, add us to your RSS reader, or subscribe to our daily digest. If you find a retraction that’s not in our database, you can let us know here. For comments or feedback, email us at team@retractionwatch.com.

Processing…Success! You're on the list.Whoops! There was an error and we couldn't process your subscription. Please reload the page and try again.in Retraction watch on 2025-12-06 11:00:00 UTC.

-

- Wallabag.it! - Save to Instapaper - Save to Pocket -

Why Leftover Pizza Is Actually Healthier: The Science of ‘Resistant Starch’ Explained

Researchers have discovered that cooling starchy foods—from pizza to rice—creates “resistant starch,” a carb that behaves like fiber and alters your blood sugar response

in Scientific American on 2025-12-05 19:00:00 UTC.

-

- Wallabag.it! - Save to Instapaper - Save to Pocket -

Is a River Alive? A Conversation with Robert Macfarlane on Nature’s Sovereignty

Scientific American sits down with nature writer Robert Macfarlane to discuss his latest book—one of our top picks of 2025—and whether a river has rights

in Scientific American on 2025-12-05 18:30:00 UTC.

-

- Wallabag.it! - Save to Instapaper - Save to Pocket -

Was the ‘Star of Bethlehem’ Really a Comet?

A scientist has identified a possible astronomical explanation for the Star of Bethlehem, as described in the Bible

in Scientific American on 2025-12-05 18:10:00 UTC.

-

- Wallabag.it! - Save to Instapaper - Save to Pocket -

A CDC panel has struck down universal newborn hepatitis B vaccination

A reshaped vaccine committee voted to scale back newborn hepatitis B shots despite decades of data showing the birth dose is safe, effective and vital.in Science News: Health & Medicine on 2025-12-05 18:01:45 UTC.

-

- Wallabag.it! - Save to Instapaper - Save to Pocket -

Plastic Pollution Will More than Double by 2040, Yielding a Garbage Truck's Worth of Waste Each Second

An estimated 280 million metric tons of plastic waste will enter the air, water, soil, and human bodies every year by 2040, data shows

in Scientific American on 2025-12-05 17:28:00 UTC.

-

- Wallabag.it! - Save to Instapaper - Save to Pocket -

Nature paper retracted after one investigation finds data errors, another finds no misconduct

Nature has retracted a paper on melanoma after an investigation by the journal found issues with data that rendered certain results statistically insignificant. A separate institutional investigation concluded misconduct wasn’t involved, the lead author says.

The research behind the article, published in April 2016, was conducted in the lab of Ashani Weeraratna, then at the Wistar Institute in Philadelphia. The paper has been cited 332 times, according to Clarivate’s Web of Science. The study investigated how the tumor microenvironment affected the spread of young versus aged cells.

An editorial investigation found some results in a figure were “no longer statistically significant, which affects the conclusions about therapy resistance,” according to the October 29 retraction notice. The inquiry also found “several errors in image and source data consistency,” as well as errors with the sample numbers given in the original study.

Other authors on the paper — of which there are 46 total — are at Yale University, Mass General Hospital, Johns Hopkins, the University of Pennsylvania, the University of California, Los Angeles, the National Institute on Aging, and other prominent institutions. Four of the authors agreed with the retraction, 28 disagreed, and 14 didn’t respond, according to the notice.

One of the authors who agreed with the retraction, Hsin-Yao Tang, was coauthor on another Wistar paper which was retracted in 2021 for data inconsistencies, as we reported at the time. He did not respond to our request for comment.

The paper received a correction in 2016 for labels in a figure that were “inadvertently reversed.” In August 2023, the journal placed an expression of concern on the paper alerting readers the “reliability of some of the data presented in this manuscript is currently in question.”

An anonymous user on PubPeer posted three comments in September 2022 pointing out inconsistencies in images provided in the raw data versus the published versions.

A different user commented the following month that the raw data for one of the figures had “many points followed by” asterisks. “If we exclude these points and graph the data, the graph and stats match the published version of the graph,” the user wrote. When the asterisked points were included, “the conclusions are no longer valid,” they added.

Other commenters noted missing data or further discrepancies between the raw and published data for the experiment.

Weeraratna, the corresponding and lead author on the paper, is now a researcher at Johns Hopkins and a member of the NIH National Cancer Advisory Board. She told Retraction Watch some results were “mistakenly labeled as outliers.” She also told us Wistar had formed an outside committee for an inquiry into the discrepancies. “The inquiry found no scientific misconduct,” she said, but added she could not discuss the matter further because of a confidentiality agreement.

Francesca Cesari, chief biological, clinical and social sciences editor for Nature, told us the institute did not contact the journal regarding the investigation. Darien Sutton, the director of media relations at Wistar, declined to comment.

The researchers repeated the experiment in 2023 “with improved, less toxic, standard-of-care inhibitors unavailable at the time of the original work,” Weeraratna said, which confirmed the paper’s original conclusions.She said the researchers sent the results of this experiment to the journal, but “Nature did not consider these.”

Cesari told us the experiments “were not an exact replication of the original work. While we carefully considered the information provided, it did not change our assessment of the concerns raised about the original publication.”

Another Nature paper from the Weeraratna lab also drew attention on PubPeer shortly after it was published in 2022, with users pointing out similar issues to the retracted paper, such as inconsistencies with raw and published data, excluded values and unexpected image similarities. Weeraratna responded to several of these comments on the PubPeer thread to explain the discrepancies. The authors published a correction in January 2025 to address the issues. Nature told us they are looking into the paper further.

Like Retraction Watch? You can make a tax-deductible contribution to support our work, follow us on X or Bluesky, like us on Facebook, follow us on LinkedIn, add us to your RSS reader, or subscribe to our daily digest. If you find a retraction that’s not in our database, you can let us know here. For comments or feedback, email us at team@retractionwatch.com.

Processing…Success! You're on the list.Whoops! There was an error and we couldn't process your subscription. Please reload the page and try again.in Retraction watch on 2025-12-05 17:23:41 UTC.

-

- Wallabag.it! - Save to Instapaper - Save to Pocket -

What If the Moon Were Cheese? John Scalzi’s Latest Book Has the Answer

Scientific American talks to the author of When the Moon Hits Your Eye, one of our best fiction picks for 2025

in Scientific American on 2025-12-05 16:15:00 UTC.

-

- Wallabag.it! - Save to Instapaper - Save to Pocket -

Psilocybin rewires specific mouse cortical networks in lasting ways

Neuronal activity induced by the psychedelic drug strengthens inputs from sensory brain areas and weakens cortico-cortical recurrent loops.in The Transmitter on 2025-12-05 16:00:57 UTC.

-

- Wallabag.it! - Save to Instapaper - Save to Pocket -

CDC Vaccine Panel Scraps Guidance for Universal Hepatitis B Shots at Birth

New guidance from the CDC’s vaccine advisory panel would do away with a decades-old universal birth dose recommendation for hepatitis B that helped cut infections by 99 percent in the U.S.

in Scientific American on 2025-12-05 15:40:00 UTC.

-

- Wallabag.it! - Save to Instapaper - Save to Pocket -

Daniel H. Wilson on Finding a Native Take on Traditional Alien Invasion Stories

Hole in the Sky, by Daniel H. Wilson, is one of Scientific American’s best fiction picks of 2025. In the novel, aliens talk through an AI headset and land in the Cherokee Nation, while the military scrambles to contain and control the unknown

in Scientific American on 2025-12-05 15:30:00 UTC.

-

- Wallabag.it! - Save to Instapaper - Save to Pocket -

Extremophile ‘Fire Amoeba’ Pushes the Boundaries of Complex Life

It was thought that complex cells couldn’t survive above a certain temperature, but a tiny amoeba has proven that assumption wrong

in Scientific American on 2025-12-05 15:15:00 UTC.

Feed list

- Brain Science with Ginger Campbell, MD: Neuroscience for Everyone

- Ankur Sinha

- Marco Craveiro

- UH Biocomputation group

- The Official PLOS Blog

- PLOS Neuroscience Community

- The Neurocritic

- Discovery magazine - Neuroskeptic

- Neurorexia

- Neuroscience - TED Blog

- xcorr.net

- The Guardian - Neurophilosophy by Mo Constandi

- Science News: Neuroscience

- Science News: AI

- Science News: Science & Society

- Science News: Health & Medicine

- Science News: Psychology

- OIST Japan

- Brain Byte - The HBP blog

- The Silver Lab

- Scientific American

- Romain Brette

- Retraction watch

- Neural Ensemble News

- Marianne Bezaire

- Forging Connections

- Yourbrainhealth

- Neuroscientists talk shop

- Brain matters the Podcast

- Brain Science with Ginger Campbell, MD: Neuroscience for Everyone

- Brain box

- The Spike

- OUPblog - Psychology and Neuroscience

- For Better Science

- Open and Shut?

- Open Access Tracking Project: news

- Computational Neuroscience

- Pillow Lab

- NeuroFedora blog

- Anna Dumitriu: Bioart and Bacteria

- arXiv.org blog

- Neurdiness: thinking about brains

- Bits of DNA

- Peter Rupprecht

- Malin Sandström's blog

- INCF/OCNS Software Working Group

- Gender Issues in Neuroscience (at Standford University)

- CoCoSys lab

- Massive Science

- Women in Neuroscience UK

- The Transmitter

- Björn Brembs

- BiasWatchNeuro

- Neurofrontiers